Vai Trò Phát Huy Dân Chủ Của An Độ Ở Châu Á

Trúc Giang MN

Trúc Giang MN

1* Vai trò của Hoa Kỳ ở châu Á

Ông Kurt Campbell, Phụ tá Ngoại trưởng Hoa Kỳ (HK) đặc trách Đông Á-Thái Bình Dương, nêu ý kiến như sau:

1. Hoa Kỳ cương quyết giữ vùng biển Đông Á và Thái Bình Dương, là khu vực hàng hải tự do và an toàn cho tất cả tàu bè trên thế giới, trong đó HK có lợi ích rất lớn.

2. HK không giữ lập trường về chủ quyền mà cũng không công nhận chủ quyền của bất cứ quốc gia nào trên vùng biển quốc tế nầy cả.

• Các quốc gia trong khu vực mong muốn HK can dự nhiều hơn nữa, vì sự hiện diện quân sự của HK sẽ tạo ra tình trạng ổn định trong khu vực, là ngăn chặn việc xử dụng quân sự của Trung Cộng trong các cuộc tranh chấp.

2. HK không giữ lập trường về chủ quyền mà cũng không công nhận chủ quyền của bất cứ quốc gia nào trên vùng biển quốc tế nầy cả.

• Các quốc gia trong khu vực mong muốn HK can dự nhiều hơn nữa, vì sự hiện diện quân sự của HK sẽ tạo ra tình trạng ổn định trong khu vực, là ngăn chặn việc xử dụng quân sự của Trung Cộng trong các cuộc tranh chấp.

2* Vai trò của Ấn Độ trong khu vực

Ấn Độ là một cường quốc đang lên, rất lo ngại về hiểm họa bành trướng của TC, hơn nữa, hai nước đã thường có những vụ xung đột biên giới mà TC đã chiếm giữ nhiều vùng lãnh thổ của Ấn Độ.

Ấn Độ giữ một vị trí quan trọng trong mắt xích ở thế tam giác để bao vây và kềm chế TC.

• Bắc Á châu: Nhật, Nam Hàn, Đài Loan

• Đông Nam Á: Úc, New Zealand và Philippines

• Nam Á: Ấn Độ

• Bắc Á châu: Nhật, Nam Hàn, Đài Loan

• Đông Nam Á: Úc, New Zealand và Philippines

• Nam Á: Ấn Độ

Ấn Độ đang trên đường phát triển trở thành một cường quốc dân chủ ở châu Á. Với vị trí chiến lược quan trọng, Ấn Độ có vai trò chủ yếu trong việc bảo vệ an ninh trên biển và dẫn dắt châu Á đến dân chủ và nhân quyền. Đó là nhận xét của chính giới Hoa Kỳ và Tây Phương.

Sự hợp tác với các quốc gia dân chủ như Nhật Bản, Nam Hàn, Úc, Tân Tây Lan và nhất là với Hoa Kỳ, Ấn Độ sẽ làm thay đổi bộ mặt của châu Á hiện nay, bộ mặt của sự đe dọa bành trướng, gây bất ổ của Trung Cộng và tay sai Bắc Hàn, Miến Điện.

Sự hợp tác với các quốc gia dân chủ như Nhật Bản, Nam Hàn, Úc, Tân Tây Lan và nhất là với Hoa Kỳ, Ấn Độ sẽ làm thay đổi bộ mặt của châu Á hiện nay, bộ mặt của sự đe dọa bành trướng, gây bất ổ của Trung Cộng và tay sai Bắc Hàn, Miến Điện.

3* Bản chất bành trướng bá quyền của Trung Cộng

Sự phát triển quân sự nhanh chóng cũng như việc tranh chấp chủ quyền trên vùng Biển Đông đã làm cho các nước láng giềng lo ngại về mối đe dọa của Bắc Kinh. Với chiến lược Biển Xanh (Lam sắc quốc thổ chiến lược), Trung Cộng đã tuyên bố chủ quyền trên một vùng biển 300 triệu km2, bao gồm vùng biển của các quốc gia như Nam Hàn, Nhật Bản, Việt Nam, Philippines, Malaysia và Brunei.

Với chiến lược Chuỗi Ngọc Trai (Nhất phiến trân châu-String of Pearls) Trung Cộng bộc lộ rõ ý đồ khống chế cả Biển Đông và một vùng của Ấn Độ Dương, trực tiếp đe dọa Ấn Độ.

Chuỗi Ngọc Trai là một vành đai trên biển bắt đầu từ đảo Hải Nam, xuống đảo Phú Lâm (Woody Island) của Hoàng Sa, tiến xuống nhóm đảo Trường Sa, qua kinh đào Kra, ôm lấy Myanmar (Miến Điện), dừng lại ở Karachi, Pakistan.

Kinh đào Kra là dự án nhiều tham vọng của Thái Lan. Con kinh nối liền Thái Bình Dương với Ấn Độ Dương ở phần đất phía Nam Thái Lan, nó nằm trên eo biển Malacca. Dự án 10 năm, huy động 30,000 công nhân, với ngân khỏa từ 20 đến 30 tỷ đô la. Trung Cộng phụ giúp thực hiện.

Cụ thể của Chuỗi Ngọc Trai là một hệ thống căn cứ hải quân thuộc các quốc gia như sau:

Chuỗi Ngọc Trai là một vành đai trên biển bắt đầu từ đảo Hải Nam, xuống đảo Phú Lâm (Woody Island) của Hoàng Sa, tiến xuống nhóm đảo Trường Sa, qua kinh đào Kra, ôm lấy Myanmar (Miến Điện), dừng lại ở Karachi, Pakistan.

Kinh đào Kra là dự án nhiều tham vọng của Thái Lan. Con kinh nối liền Thái Bình Dương với Ấn Độ Dương ở phần đất phía Nam Thái Lan, nó nằm trên eo biển Malacca. Dự án 10 năm, huy động 30,000 công nhân, với ngân khỏa từ 20 đến 30 tỷ đô la. Trung Cộng phụ giúp thực hiện.

Cụ thể của Chuỗi Ngọc Trai là một hệ thống căn cứ hải quân thuộc các quốc gia như sau:

1. Căn cứ hải quân ở cảng Gwadar, Pakistan

2. Căn cứ Marao, Maldives (Quần đảo, cách Sri Lanka 700 km. Dân số 349, 106 người)

3. Căn cứ Hambantota, Sri Lanka (Đảo ngoài khơi phía Nam, cách bờ biển Ấn Độ 31km)

4. Căn cứ ở hải cảng Chittagong, Bangladesh

5. Căn cứ ở hải cảng Ile Cocos, Myanmar

6. Căn cứ ở hải cảng Sihanoukville, Campuchia

2. Căn cứ Marao, Maldives (Quần đảo, cách Sri Lanka 700 km. Dân số 349, 106 người)

3. Căn cứ Hambantota, Sri Lanka (Đảo ngoài khơi phía Nam, cách bờ biển Ấn Độ 31km)

4. Căn cứ ở hải cảng Chittagong, Bangladesh

5. Căn cứ ở hải cảng Ile Cocos, Myanmar

6. Căn cứ ở hải cảng Sihanoukville, Campuchia

Xây dựng một màng lưới hải quân như thế, rõ ràng là Trung Cộng muốn bao vây Ấn Độ ở phía Nam. Trong khi một lực lượng bộ binh trên 100,000, trang bị vũ khí hiện đại, án ngữ một biên giới dài trên 4,000 km ở phía dãy Himalaya, tạo ra một gọng kềm sẵn sàng tấn công Ấn Độ.

Để thực hiện chiến lược bành trướng trên biển, Trung Cộng (TC) đã phát triển mạnh mẽ hải quân, chế tạo Hàng Không Mẫu Hạm (HKMH), sản xuất hỏa tiễn tiêu diệt HKMH. Các nước trong khu vực rất lo ngại, thi nhau mua sắm vũ khí để hiện đại hóa quân đội.

Trước mối đe dọa của Trung Cộng, sự hiện diện của cường quốc Hoa Kỳ rất cần thiết ở châu Á.

Để thực hiện chiến lược bành trướng trên biển, Trung Cộng (TC) đã phát triển mạnh mẽ hải quân, chế tạo Hàng Không Mẫu Hạm (HKMH), sản xuất hỏa tiễn tiêu diệt HKMH. Các nước trong khu vực rất lo ngại, thi nhau mua sắm vũ khí để hiện đại hóa quân đội.

Trước mối đe dọa của Trung Cộng, sự hiện diện của cường quốc Hoa Kỳ rất cần thiết ở châu Á.

4* Hoa Kỳ khuyến khích vai trò của Ấn Độ ở châu Á

Ngày 20-7-2011, đài BBC loan tin, Ngoại trưởng Clinton đã đọc bài diễn văn ở thành phố Chennai, Ấn Độ, cho rằng, Ấn Độ cần phải tăng cường sức mạnh chính trị cho xứng đáng với sự phát triển kinh tế. HK mong rằng mối quan hệ giữa hai nước sẽ tạo dựng đối tác cho thế kỷ 21. Các viên chức HK cho rằng sự hợp tác giữa Washington và New Delhi sẽ làm thay đổi diện mạo châu Á.

Tháng 11 năm 2010, Tổng thống Barack Obama đã thăm Ấn Độ và công khai tuyên bố ủng hộ Ấn Độ vào ghế Hội viên thường trực của Hội Đồng Bảo An LHQ. HK muốn thấy Ấn Độ, một quốc gia đông dân nhất trong các quốc gia dân chủ, trở thành một đồng minh để cùng HK tham gia giải quyết những vấn đề toàn cầu. Tính tương đồng của hai nước là bảo vệ an ninh chung trên biển và dẫn dắt châu Á đến dân chủ và nhân quyền.

Trong cuộc viếng thăm 3 ngày hôm 19-7-2011, bà Clinton tiến hành hàng loạt các cuộc hội đàm với Thủ tướng Manmohan Singh, Bộ trưởng ngoại giao M. Christina và cố vấn an ninh quốc gia Ấn Độ. Các chủ đề hàng đầu là:

- Phát triển thương mại song phương

- Hợp tác hạt nhân dân sự

- Tình hình an ninh ở Afghanistan. Ấn Độ lo ngại khi HK rút quân, Tổng thống Karzai không đủ khả năng tự vệ chống lại quân Taliban, bất ổn xảy ra làm ảnh hưởng tới nước láng giềng Ấn Độ.

- Đặc biệt là việc chống khủng bố. Bà Clinton khẳng định, HK và Ấn Độ là đồng minh trong cuộc chống các tổ chức cực đoan, kích động bạo lực. HK sẽ cung cấp sự hỗ trợ đầy đủ giúp Ấn Độ ngăn chặn những vụ tấn công khủng bố.

- Phát triển thương mại song phương

- Hợp tác hạt nhân dân sự

- Tình hình an ninh ở Afghanistan. Ấn Độ lo ngại khi HK rút quân, Tổng thống Karzai không đủ khả năng tự vệ chống lại quân Taliban, bất ổn xảy ra làm ảnh hưởng tới nước láng giềng Ấn Độ.

- Đặc biệt là việc chống khủng bố. Bà Clinton khẳng định, HK và Ấn Độ là đồng minh trong cuộc chống các tổ chức cực đoan, kích động bạo lực. HK sẽ cung cấp sự hỗ trợ đầy đủ giúp Ấn Độ ngăn chặn những vụ tấn công khủng bố.

Bộ trưởng Robert Gates của HK cũng đến thăm bộ trưởng quốc phòng Ấn Độ, A.K. Anthony. Ông Gates tuyên bố “Chúng tôi đã bàn về an ninh ở Ấn Độ Dương và mối đe dọa quân sự của Trung Cộng.” Việc TC phiêu lưu tấn công không gian mạng (www) đã gây lo ngại cho toàn thế giới. Ấn Độ tố cáo TC đã tấn công những trang Web quan trọng của họ ngay trong lúc Google cũng tuyên bố TC tấn công tương tự.

Trung Cộng ngày nay thật sự là một mối đe dọa cho an ninh thế giới.

Trung Cộng ngày nay thật sự là một mối đe dọa cho an ninh thế giới.

5* Nước Ấn Độ

Ấn Độ tên cổ là Thiên Trúc, là một quốc gia ở phía Nam châu Á, chiếm hầu hết diện tích của bán đảo Ấn Độ, nằm trong Ấn Độ Dương.(Indian Ocean)

Là thuộc địa của Anh, thu hồi độc lập ngày 15-8-1947 do công tranh đấu bất bạo động của ông Mohanda Gandhi.

Anh quốc đã tách Ấn Độ ra thành 2 quốc gia vì lý do khác biệt về tôn giáo. Một quốc gia tên là Ấn Độ (India) gồm đa số theo Ấn Độ giáo (Hindu), và một quốc gia Hồi giáo là Pakistan. Nước Pakistan lại gồm 2 phần, phía Đông là Đông Pakistan (Đông Hồi) ngày nay làBangladesh. Phần phía Tây Pakistan (Tây Hồi) ngày nay là nước Cộng hòa Hồi giáo Pakistan. Đông và Tây Pakistan cách nhau 2,000 km, nằm 2 bên nước Ấn Độ.

Như vậy, 3 quốc gia hiện nay là Ấn Độ, Pakistan và Bangladesh đều xuất xứ từ một nước Ấn Độ trước kia. Vì có nhiều sắc tộc khác nhau, nhiều tôn giáo khác nhau, nên việc phân chia không có ảnh hưởng gì nhiều tới tinh thần dân tộc cả.

Anh quốc đã tách Ấn Độ ra thành 2 quốc gia vì lý do khác biệt về tôn giáo. Một quốc gia tên là Ấn Độ (India) gồm đa số theo Ấn Độ giáo (Hindu), và một quốc gia Hồi giáo là Pakistan. Nước Pakistan lại gồm 2 phần, phía Đông là Đông Pakistan (Đông Hồi) ngày nay làBangladesh. Phần phía Tây Pakistan (Tây Hồi) ngày nay là nước Cộng hòa Hồi giáo Pakistan. Đông và Tây Pakistan cách nhau 2,000 km, nằm 2 bên nước Ấn Độ.

Như vậy, 3 quốc gia hiện nay là Ấn Độ, Pakistan và Bangladesh đều xuất xứ từ một nước Ấn Độ trước kia. Vì có nhiều sắc tộc khác nhau, nhiều tôn giáo khác nhau, nên việc phân chia không có ảnh hưởng gì nhiều tới tinh thần dân tộc cả.

Ấn Độ có biên giới chung với Pakistan, Bangladesh, Trung Cộng, Myanmar (Miến Điện), Nepal, Bhutan và Afghanistan.

Diện tích:3,287,590 km2

Dân số: 1.19 tỷ (2006). Thứ nhì thế giới, sau Trung Cộng.

Thủ đô: New Delhi

Thành phố lớn nhất: Mumbai (Tên cũ Bombay)

Ngôn ngữ chính: Tiếng Anh. Tiếng Hindi và 21 thứ tiếng khác.

Tổng thống: Pratibha Patil

Thủ tướng: Manmohan Singh

Tôn giáo: Ấn Độ giáo (Hindu) 80% dân số. Hồi giáo 13.4%, Phật giáo 0.76%, đạo Sikh 1.84%.

Kinh tế đứng hàng thứ tư thế giới.

GDP đầu người: 3,400 USD/per capita.

Ấn Độ là một quốc gia dân chủ đại nghị (Quốc hội). 3 ngành lập pháp, hành pháp và tư pháp độc lập nhau. Gồm 28 bang và 7 lãnh thổ.

Dãy núi Himalaya nằm trên ranh giới với TC. Ngọn Everest cao nhất thế giới, 8,850m.

Diện tích:3,287,590 km2

Dân số: 1.19 tỷ (2006). Thứ nhì thế giới, sau Trung Cộng.

Thủ đô: New Delhi

Thành phố lớn nhất: Mumbai (Tên cũ Bombay)

Ngôn ngữ chính: Tiếng Anh. Tiếng Hindi và 21 thứ tiếng khác.

Tổng thống: Pratibha Patil

Thủ tướng: Manmohan Singh

Tôn giáo: Ấn Độ giáo (Hindu) 80% dân số. Hồi giáo 13.4%, Phật giáo 0.76%, đạo Sikh 1.84%.

Kinh tế đứng hàng thứ tư thế giới.

GDP đầu người: 3,400 USD/per capita.

Ấn Độ là một quốc gia dân chủ đại nghị (Quốc hội). 3 ngành lập pháp, hành pháp và tư pháp độc lập nhau. Gồm 28 bang và 7 lãnh thổ.

Dãy núi Himalaya nằm trên ranh giới với TC. Ngọn Everest cao nhất thế giới, 8,850m.

6* Lực lượng vũ trang Ấn Độ

Lực lương vũ trang gồm lục quân (bộ binh, thiết giáp, pháo binh…), hải quân, không quân, biên phòng và bán quân sự.

Tất cả quân nhân Ấn Độ đều là người tình nguyện. Tổng thống là tư lịnh tối cao quân đội.

6.1. Lục quân Ấn Độ

Lục quân là ngành bộ chiến, lớn nhất trong lực lượng vũ trang Ấn Độ. Tổ chức các đơn vị từ quân đoàn, sư đoàn, trung đoàn, tiểu đoàn xuống đến tiểu đội.

Quân số lục quân:

Tại ngũ: 1,325,000

Trừ bị: 2,142,821

Số sư đoàn: 37 sư đoàn, gồm các sư đoàn bộ binh, thiết giáp, pháo binh…Mỗi sư đoàn có 15,000 quân chiến đấu và 8,000 quân yểm trợ.

Số trung đoàn độc lập: 135

Số tiểu đoàn độc lập: 10. Gồm quân dù và lực lượng đặc biệt

Vũ khí

- Xe tăng các loại: 5,000

- Súng đại bác: 11,258 khẩu

- Phi cơ lục quân: 1,600 chiếc

- Trực thăng: 820

- Phi cơ không người lái các loại: 64

- Phi cơ vận tải: 197

- Hoả tiễn đạn đạo (Ballistic Missile): 100 (loại Agni)

- Hoả tiễn đạn đạo chiến thuật: 1,000 (loại Prithvi)

- Hỏa tiễn hành trình (Cruise): 1,000 (loại Bramos)

- Hoả tiễn đất đối không: 100,000.

Quân số lục quân:

Tại ngũ: 1,325,000

Trừ bị: 2,142,821

Số sư đoàn: 37 sư đoàn, gồm các sư đoàn bộ binh, thiết giáp, pháo binh…Mỗi sư đoàn có 15,000 quân chiến đấu và 8,000 quân yểm trợ.

Số trung đoàn độc lập: 135

Số tiểu đoàn độc lập: 10. Gồm quân dù và lực lượng đặc biệt

Vũ khí

- Xe tăng các loại: 5,000

- Súng đại bác: 11,258 khẩu

- Phi cơ lục quân: 1,600 chiếc

- Trực thăng: 820

- Phi cơ không người lái các loại: 64

- Phi cơ vận tải: 197

- Hoả tiễn đạn đạo (Ballistic Missile): 100 (loại Agni)

- Hoả tiễn đạn đạo chiến thuật: 1,000 (loại Prithvi)

- Hỏa tiễn hành trình (Cruise): 1,000 (loại Bramos)

- Hoả tiễn đất đối không: 100,000.

6.2. Hải quân Ấn Độ

Quân số tại ngũ: 96,000. Bao gồm 5,000 thuộc không lực HQ

Tàu chiến: 170. Bao gồm 1 Hàng không mẫu hạm INS Viraat với 30 chiến đấu cơ MiG-29 và Sea Harrier.

6.2.1. Không lực hải quânTổng số phi cơ chiến đấu: 250 chiếc (MiG-29 và Sea Harrier)

Ngoài ra, còn các loại chiến tranh điện tử, thám thính, vận tải, huấn luyện…

6.2.2. Hàng không mẫu hạmChiếc INS Viraat (INS=India Naval Ship) do Anh bán lại hồi năm 1987. Sau nhiều lần sửa chữa và nâng cấp, sẽ bị phế thải vào năm 2015.

HKMH Viraat.

Dài: 226.5m

Tốc độ tối đa: 51.9 km/giờ

Tầm hoạt động: 12,068km

Thủy thủ đoàn: 160 sĩ quan, 1,400 thủy thủ

Sức chở: 30 phi cơ MiG-29 và Sea Harrier (Anh)

Sea Harrier là loại phi cơ VTOL/STOVL, là phi cơ chiến đấu đa năng: không chiến, tấn công mặt đất (bỏ bom) và thám thính. Thuộc thế hệ 4.

VTOL: Vertical Take-Off and Landing. Cất cánh thẳng đứng, như trực thăng.

STOVL: Short Take-Off and Vertical Landing. Cất cánh với phi đạo ngắn và đáp xuống thẳng đứng, như trực thăng.

6.2.3. Tàu ngầm- 16 tàu ngầm chạy bằng dầu Diesel.

- 1 tàu ngầm chạy bằng năng lượng hạt nhân do Ấn Độ đóng, tên Arihant, nặng 6,000 tấn. Lò phản ứng 85 megawatts, sẽ đưa vào xử dụng năm 2015

Ấn Độ đặt mua của Nga một tàu ngầm hạt nhân tên Nerpa, lặn sâu 600m, hoạt động 100 ngày trong lòng biển.

6.3. Không quân Ấn Độ

Không quân Ấn Độ trang bị phi cơ các nước: Nga, Anh, Pháp, Do Thái và Hoa Kỳ.

Quân số: 170,000

Tổng số phi cơ các loại: 1,625 chiếc

Gồm các loại SU-30 (thế hệ 4.5), HAL Jeja (4.5), MiG-29 (4), Dassault Mirage 2000 (Pháp, thế hệ 4), MiG-21 (2), MiG-27 (thế hệ 2).

Các loại phi cơ cảnh báo sớm, chiến tranh điện tử, tiếp nhiên liệu trên không, vận tải.

Trong chương trình hiện đại hóa quân đội, Ấn Độ dành ra ngân khỏan 120 tỷ USD để mua sắm vũ khí từ 2012 đến 2017.

Mua 10 phi cơ vận tải hiện đại nhất của HK là chiếc Boeing C-17 Globemaster III với giá 4.1 tỷ USD. Chiếc C-17 có thể chở xe tăng M-1 Abram (69 tấn), xe tăng M2, M3 Bradley, hoặc 6 trực thăng UH-60 Blackhawk và AH-64 Apache.

Chở 200 lính dù với trang bị. Chở chiếc Limousine của TT/HK ra ngoại quốc khi TT công du nước ngoài.

Tàu chiến: 170. Bao gồm 1 Hàng không mẫu hạm INS Viraat với 30 chiến đấu cơ MiG-29 và Sea Harrier.

6.2.1. Không lực hải quânTổng số phi cơ chiến đấu: 250 chiếc (MiG-29 và Sea Harrier)

Ngoài ra, còn các loại chiến tranh điện tử, thám thính, vận tải, huấn luyện…

6.2.2. Hàng không mẫu hạmChiếc INS Viraat (INS=India Naval Ship) do Anh bán lại hồi năm 1987. Sau nhiều lần sửa chữa và nâng cấp, sẽ bị phế thải vào năm 2015.

HKMH Viraat.

Dài: 226.5m

Tốc độ tối đa: 51.9 km/giờ

Tầm hoạt động: 12,068km

Thủy thủ đoàn: 160 sĩ quan, 1,400 thủy thủ

Sức chở: 30 phi cơ MiG-29 và Sea Harrier (Anh)

Sea Harrier là loại phi cơ VTOL/STOVL, là phi cơ chiến đấu đa năng: không chiến, tấn công mặt đất (bỏ bom) và thám thính. Thuộc thế hệ 4.

VTOL: Vertical Take-Off and Landing. Cất cánh thẳng đứng, như trực thăng.

STOVL: Short Take-Off and Vertical Landing. Cất cánh với phi đạo ngắn và đáp xuống thẳng đứng, như trực thăng.

6.2.3. Tàu ngầm- 16 tàu ngầm chạy bằng dầu Diesel.

- 1 tàu ngầm chạy bằng năng lượng hạt nhân do Ấn Độ đóng, tên Arihant, nặng 6,000 tấn. Lò phản ứng 85 megawatts, sẽ đưa vào xử dụng năm 2015

Ấn Độ đặt mua của Nga một tàu ngầm hạt nhân tên Nerpa, lặn sâu 600m, hoạt động 100 ngày trong lòng biển.

6.3. Không quân Ấn Độ

Không quân Ấn Độ trang bị phi cơ các nước: Nga, Anh, Pháp, Do Thái và Hoa Kỳ.

Quân số: 170,000

Tổng số phi cơ các loại: 1,625 chiếc

Gồm các loại SU-30 (thế hệ 4.5), HAL Jeja (4.5), MiG-29 (4), Dassault Mirage 2000 (Pháp, thế hệ 4), MiG-21 (2), MiG-27 (thế hệ 2).

Các loại phi cơ cảnh báo sớm, chiến tranh điện tử, tiếp nhiên liệu trên không, vận tải.

Trong chương trình hiện đại hóa quân đội, Ấn Độ dành ra ngân khỏan 120 tỷ USD để mua sắm vũ khí từ 2012 đến 2017.

Mua 10 phi cơ vận tải hiện đại nhất của HK là chiếc Boeing C-17 Globemaster III với giá 4.1 tỷ USD. Chiếc C-17 có thể chở xe tăng M-1 Abram (69 tấn), xe tăng M2, M3 Bradley, hoặc 6 trực thăng UH-60 Blackhawk và AH-64 Apache.

Chở 200 lính dù với trang bị. Chở chiếc Limousine của TT/HK ra ngoại quốc khi TT công du nước ngoài.

7* Quan hệ giữa Ấn Độ và Trung Cộng

Năm 1957

Trung Cộng ngang ngược xây dựng trục giao thông trên phần đất tranh chấp Aksai Chin.

Tháng 10 năm 1962

Trung Cộng đưa 9 sư đoàn đến đóng ở biên giới 3,325 km, vùng núi Himalaya. Chiến tranh bùng nổ ác liệt. Kết quả Ấn Độ thua trận, bị TC chiếm phần đất sâu 50km ở Aksai Chin, diện tích 38,000Km2 ở cao độ 5,000m

Tháng 6 năm 2009

Trung Cộng đưa một số đông quân lính đến tập trung tại biên giới. Ấn Độ điều 4 sư đoàn với đại bác 155 ly ra phòng thủ.

TC bèn mang tàu chiến đến Ấn Độ Dương, được sự yểm trợ của các căn cứ HQ Myanmar, Bangladesh, Pakistan và Sri Lanka, là những căn cứ HQ nằm trong Chuỗi Ngọc Trai của TC.

Ấn Độ ở vào thế yếu, không dám xung trận.

Các nhà phân tích Ấn Độ nhận định, “TC cố ý kềm chế, không cho Ấn Độ trở thành một cường quốc về kinh tế và quân sự”.

Trong suốt 25 năm qua, Ấn Độ đã mất một số lãnh thổ về tay TC.

Ngày 7-9-2010

Sự căng thẳng giữa Ấn Độ và TC bổng nhiên gia tăng mạnh mẽ tại khu vực phía Nam dãy Himalaya là vùng Kashmir. Thủ tướng Manmohan Singh là người ôn hòa đã tuyên bố cứng rắn, “Trung Quốc muốn lấn sân tại Nam Á. Người Tàu ngày càng tự tin vào bản thân, họ muốn kìm hãm Ấn Độ. Thật khó mà nói được điều gì sắp xảy ra, nhưng điều quan trọng là phải chuẩn bị.”

Năm 1962, Ấn Độ phải nhường một ngôi làng ở Đông Bắc là Arunachal Pradesh mà TC gọi là Nam Tây Tạng.

Ngày 15-9-2010

Tờ Washington Post loan tin, có 11,000 binh sĩ TC có mặt tại tại vùng phía Bắc Gilgit Balistan, do Pakistan cai quản mà Ấn Độ đang đòi chủ quyền. Pakistan viện cớ rằng người Tàu là những kỹ sư và công nhân đến giúp khắc phục hậu quả của trận lụt khủng khiếp vừa qua. Nhưng thật ra, TC đưa quân đến giúp Pakistan chống lại Ấn Độ. Thông qua hành động đó, Viện Institute for Defense Studies and Analysis tai New Delhi nêu nhận xét: “Trước kia, Ấn Độ coi TQ là mối đe dọa, ngày nay thì trái lại, TQ coi Ấn Độ là mối đe dọa vì Ấn Độ đã phát triển kinh tế và hiện đại hóa quốc phòng”.

Trung Cộng ngang ngược xây dựng trục giao thông trên phần đất tranh chấp Aksai Chin.

Tháng 10 năm 1962

Trung Cộng đưa 9 sư đoàn đến đóng ở biên giới 3,325 km, vùng núi Himalaya. Chiến tranh bùng nổ ác liệt. Kết quả Ấn Độ thua trận, bị TC chiếm phần đất sâu 50km ở Aksai Chin, diện tích 38,000Km2 ở cao độ 5,000m

Tháng 6 năm 2009

Trung Cộng đưa một số đông quân lính đến tập trung tại biên giới. Ấn Độ điều 4 sư đoàn với đại bác 155 ly ra phòng thủ.

TC bèn mang tàu chiến đến Ấn Độ Dương, được sự yểm trợ của các căn cứ HQ Myanmar, Bangladesh, Pakistan và Sri Lanka, là những căn cứ HQ nằm trong Chuỗi Ngọc Trai của TC.

Ấn Độ ở vào thế yếu, không dám xung trận.

Các nhà phân tích Ấn Độ nhận định, “TC cố ý kềm chế, không cho Ấn Độ trở thành một cường quốc về kinh tế và quân sự”.

Trong suốt 25 năm qua, Ấn Độ đã mất một số lãnh thổ về tay TC.

Ngày 7-9-2010

Sự căng thẳng giữa Ấn Độ và TC bổng nhiên gia tăng mạnh mẽ tại khu vực phía Nam dãy Himalaya là vùng Kashmir. Thủ tướng Manmohan Singh là người ôn hòa đã tuyên bố cứng rắn, “Trung Quốc muốn lấn sân tại Nam Á. Người Tàu ngày càng tự tin vào bản thân, họ muốn kìm hãm Ấn Độ. Thật khó mà nói được điều gì sắp xảy ra, nhưng điều quan trọng là phải chuẩn bị.”

Năm 1962, Ấn Độ phải nhường một ngôi làng ở Đông Bắc là Arunachal Pradesh mà TC gọi là Nam Tây Tạng.

Ngày 15-9-2010

Tờ Washington Post loan tin, có 11,000 binh sĩ TC có mặt tại tại vùng phía Bắc Gilgit Balistan, do Pakistan cai quản mà Ấn Độ đang đòi chủ quyền. Pakistan viện cớ rằng người Tàu là những kỹ sư và công nhân đến giúp khắc phục hậu quả của trận lụt khủng khiếp vừa qua. Nhưng thật ra, TC đưa quân đến giúp Pakistan chống lại Ấn Độ. Thông qua hành động đó, Viện Institute for Defense Studies and Analysis tai New Delhi nêu nhận xét: “Trước kia, Ấn Độ coi TQ là mối đe dọa, ngày nay thì trái lại, TQ coi Ấn Độ là mối đe dọa vì Ấn Độ đã phát triển kinh tế và hiện đại hóa quốc phòng”.

8* Ấn Độ vùng dậy

8.1. Ấn Độ liên minh với Nga

70% vũ khí của Ấn Dộ là do Liên Xô trước kia và Nga ngày nay cung cấp. Ấn Độ và Nga hợp tác sản xuất động cơ hỏa tiễn siêu âm Brahmos tại bang Kerala phía Đông Nam Ấn Độ.

Ấn Độ đang đặt mua 260 phi cơ chiến đấu thế hệ 5 của Nga trị giá từ 25 đến 30 tỷ USD. Thỏa thuận được ký hồi tháng 12 năm 2010 trong lúc Tổng thống Nga Dmitry Anatolyevich Medvedev viếng Ấn Độ.

Tổng thống Pháp Nicolas Sarkozy và Thủ tướng Anh David Cameron cũng đến thăm Ấn Độ để ký những chương trình hợp tác.

8.2. Ấn Độ liên minh với Hoa Kỳ

Ngày 21-11-2009, Thủ tướng Manmohan Singh viếng HK trong 5 ngày để thảo luận các vấn đề song phương, quan trọng nhất là thiết lập một khung chiến lược Trung Á và Nam Á châu.

Một hiệp ước hạt nhân dân sự được ký kết. Và việc HK bán cho Ấn Độ những thiết bị cao cấp để trang bị cho quân đội Ấn.

Dân số Ấn Độ 1.1 tỷ, có nhiều lợi điểm hơn TC, là chế độ đại nghị, dân chủ, tự do. Đội ngũ chuyên viên kỹ thuật cao, thông thạo Anh ngữ. Sinh viên Ấn không gặp những khó khăn về ngôn ngữ trong các đại học HK. Hiện có 700,000 bác sĩ Ấn Độ đang hành nghề ở HK.

Công ty Microsoft cũng đã mở nhiều chi nhánh máy vi tính ở bang Bangalore của Ấn.

Ấn Độ và HK cũng tham gia tập trận hải quân chung, được tổ chức ở gần Đài Loan và gần bờ biển của Trung Cộng.

8.3. Ấn Độ liên minh với Nhật

Hành động hung hăng côn đồ của TC đối với Nhật trong vụ tranh chấp đảo Sensaku/Điếu Ngư, đã khiến cho Nhật tăng cường hợp tác với Ấn Độ.

Ngày 28-6-2010, đài Á Châu Tự Do loan tin, Nhật bắt đầu đàm phán với Ấn Độ về việc xuất cảng kỹ thuật điện tử do những hảng lớn như Toshiba, Hitachi sản xuất. Các hảng xe hơi Toyota và Nissan cũng đã mở những xưởng ráp xe ở Ấn Độ.

Ngoài ra, ASEAN và Úc cũng hợp tác với Ấn Độ trong việc phòng thủ chống Trung Cộng.

Đa số các nước ASEAN đoàn kết chống TC. Tổng thống Philippines Benigno Aquino III tuyên bố: “Khi ASEAN đàm phán với bất cứ thế lực nào bên ngoài, thì tiếng nói của ASEAN là một”.

Nguyên thứ trưởng quốc phòng Úc, ông Paul Dibb, thuộc Viện Nghiên Cứu Chiến Lược đại học Quốc Gia Úc, viết trên tờ The Australian: “Chẳng còn bao lâu nữa, liên minh hải quân Tây Phương hoạt động ở châu Á-Thái Bình Dương liên kết lại với nhau để kềm chế sự gia tăng ảnh hưởng của TQ. Liên minh gồm tàu chiến của HK, Nhật, Úc, bắt buộc TQ phải tôn trọng luật hàng hải quốc tế, không ngoại trừ khả năng dạy cho TQ một bài học”.

Úc mua 70 tỷ USD vũ khí để canh tân quân đội Úc trong vòng 20 năm, đặc biệt là để đối phó với Trung Cộng. Úc mua hỏa tiễn tầm xa, tăng gấp đôi số tàu ngầm lên 12 chiếc. Mua 100 phi cơ chiến đấu hiện đại nhất của HK là F-35, đồng thời mua thêm 8 chiến hạm.

Ngày 21-2-2011, công ty dầu khí Anh quốc British Petroleum (BP) và công ty Reliance Industries của Ấn Độ đã ký một thỏa thuận 20 tỷ USD cho dự án dầu lửa và khí đốt của Ấn Độ.

8.4. Ấn Độ o bế Việt Nam

Tháng 10 năm 2010, Ấn Độ và VN công bố một loạt các hợp tác quân sự như giúp VN huấn luyện nâng cấp khả năng quốc phòng, giúp nâng cấp 100 phi cơ MiG-21, tham gia huấn luyện hỗn hợp, trao đổi kinh nghiệm tác chiến rừng núi.

70% vũ khí của Ấn Dộ là do Liên Xô trước kia và Nga ngày nay cung cấp. Ấn Độ và Nga hợp tác sản xuất động cơ hỏa tiễn siêu âm Brahmos tại bang Kerala phía Đông Nam Ấn Độ.

Ấn Độ đang đặt mua 260 phi cơ chiến đấu thế hệ 5 của Nga trị giá từ 25 đến 30 tỷ USD. Thỏa thuận được ký hồi tháng 12 năm 2010 trong lúc Tổng thống Nga Dmitry Anatolyevich Medvedev viếng Ấn Độ.

Tổng thống Pháp Nicolas Sarkozy và Thủ tướng Anh David Cameron cũng đến thăm Ấn Độ để ký những chương trình hợp tác.

8.2. Ấn Độ liên minh với Hoa Kỳ

Ngày 21-11-2009, Thủ tướng Manmohan Singh viếng HK trong 5 ngày để thảo luận các vấn đề song phương, quan trọng nhất là thiết lập một khung chiến lược Trung Á và Nam Á châu.

Một hiệp ước hạt nhân dân sự được ký kết. Và việc HK bán cho Ấn Độ những thiết bị cao cấp để trang bị cho quân đội Ấn.

Dân số Ấn Độ 1.1 tỷ, có nhiều lợi điểm hơn TC, là chế độ đại nghị, dân chủ, tự do. Đội ngũ chuyên viên kỹ thuật cao, thông thạo Anh ngữ. Sinh viên Ấn không gặp những khó khăn về ngôn ngữ trong các đại học HK. Hiện có 700,000 bác sĩ Ấn Độ đang hành nghề ở HK.

Công ty Microsoft cũng đã mở nhiều chi nhánh máy vi tính ở bang Bangalore của Ấn.

Ấn Độ và HK cũng tham gia tập trận hải quân chung, được tổ chức ở gần Đài Loan và gần bờ biển của Trung Cộng.

8.3. Ấn Độ liên minh với Nhật

Hành động hung hăng côn đồ của TC đối với Nhật trong vụ tranh chấp đảo Sensaku/Điếu Ngư, đã khiến cho Nhật tăng cường hợp tác với Ấn Độ.

Ngày 28-6-2010, đài Á Châu Tự Do loan tin, Nhật bắt đầu đàm phán với Ấn Độ về việc xuất cảng kỹ thuật điện tử do những hảng lớn như Toshiba, Hitachi sản xuất. Các hảng xe hơi Toyota và Nissan cũng đã mở những xưởng ráp xe ở Ấn Độ.

Ngoài ra, ASEAN và Úc cũng hợp tác với Ấn Độ trong việc phòng thủ chống Trung Cộng.

Đa số các nước ASEAN đoàn kết chống TC. Tổng thống Philippines Benigno Aquino III tuyên bố: “Khi ASEAN đàm phán với bất cứ thế lực nào bên ngoài, thì tiếng nói của ASEAN là một”.

Nguyên thứ trưởng quốc phòng Úc, ông Paul Dibb, thuộc Viện Nghiên Cứu Chiến Lược đại học Quốc Gia Úc, viết trên tờ The Australian: “Chẳng còn bao lâu nữa, liên minh hải quân Tây Phương hoạt động ở châu Á-Thái Bình Dương liên kết lại với nhau để kềm chế sự gia tăng ảnh hưởng của TQ. Liên minh gồm tàu chiến của HK, Nhật, Úc, bắt buộc TQ phải tôn trọng luật hàng hải quốc tế, không ngoại trừ khả năng dạy cho TQ một bài học”.

Úc mua 70 tỷ USD vũ khí để canh tân quân đội Úc trong vòng 20 năm, đặc biệt là để đối phó với Trung Cộng. Úc mua hỏa tiễn tầm xa, tăng gấp đôi số tàu ngầm lên 12 chiếc. Mua 100 phi cơ chiến đấu hiện đại nhất của HK là F-35, đồng thời mua thêm 8 chiến hạm.

Ngày 21-2-2011, công ty dầu khí Anh quốc British Petroleum (BP) và công ty Reliance Industries của Ấn Độ đã ký một thỏa thuận 20 tỷ USD cho dự án dầu lửa và khí đốt của Ấn Độ.

8.4. Ấn Độ o bế Việt Nam

Tháng 10 năm 2010, Ấn Độ và VN công bố một loạt các hợp tác quân sự như giúp VN huấn luyện nâng cấp khả năng quốc phòng, giúp nâng cấp 100 phi cơ MiG-21, tham gia huấn luyện hỗn hợp, trao đổi kinh nghiệm tác chiến rừng núi.

9* Trung Cộng gây chiến tranh biên giới với láng giềng

Sau khi lên cầm quyền năm 1949, Mao Trạch Đông tuyên bố Tây Tạng thuộc về Trung Cộng và tiếp theo đó, tiến hành những cuộc chiến tranh biên giới với các nước láng giềng. Chiến tranh Ấn Độ - Trung Cộng năm 1962, chiến tranh Trung-Xô năm 1969, đánh cướp Hoàng Sa năm 1974, tấn công biên giới Bắc VN năm 1979, trận chiến bí mật ở Lão Sơn, VN năm 1988.

Về biên giới, TC có đường biên giới trên bộ tổng cộng 22,000km tiếp giáp với 14 quốc gia như Bắc Hàn, Ấn Độ, Nga, VN…

Chủ nghĩa bành trướng Đại Hán đã cai trị VN hơn 10 thế kỷ, kể từ thế kỷ thứ 2 TCN đến những thế kỷ sau, qua các triều đại Tần, Triệu, Hán, Ngô, Đường, Tống, Nguyên, Minh, Thanh và Mao Trạch Đông của đảng CSTQ.

9.1. Trung Cộng chiếm Tây Tạng

Tháng 10 năm 1950

TC đem 40,000 quân tấn công Tây Tạng cùng một lúc ở 6 vị trí, chỉ trong 2 ngày, TC giết trên 4,000 người trong một đạo quân bé nhỏ 8,000 người của Tây Tạng.

Ngày 9-9-1951

TC đem 23,000 quân chiếm đóng và cai trị Tây Tạng từ đó đến nay.

Tháng 3 năm 1959

Một cuộc nổi dậy chống TC bị thất bại ở Thủ đô Lhassa, Đức Đạt Lai Lạt Ma và hàng ngàn người Tây Tạng đến nương náu ở vùng Tây Bắc Ấn Độ, tập trung ở bang Himachal Pradesh, điều nầy khiến cho TC khó chịu.

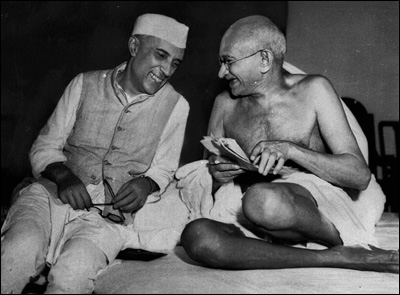

Việc TC chiếm Tây Tạng là một đòn nặng đối với bản thân Thủ tướng Jawaharlal Nehru của Ấn Độ vì ông chủ trương “Thuyết Sống chung hoà bình”. Tuy bị chỉ trích là ngây thơ và yếu hèn, nhưng ông Nehru vẫn cố gắng “dĩ hoà vi quý”, nhường nhịn, lập bang giao với TC. TC nêu khẩu hiệu “Hindi-Chini bhai-bhai”, có nghĩa là “Ấn Độ và Trung Cộng là anh em”. Cũng giống như khẩu hiệu 16 chữ vàng và 4 tốt đối với VN hiện nay.

Nhưng tình huynh đệ chỉ kéo dài được vài năm, thì TC đem quân tấn công chiếm lãnh thổ Ấn Độ.

9.2. Trung Cộng đánh chiếm lãnh thổ Ấn Độ năm 1962

Nguyên nhân chính là việc tranh chấp biên giới vùng Aksai Chin và bang Arunachal Pradesh mà TC gọi là Nam Tây Tạng. Ngoài ra, còn những nguyên nhấn khác, như hàng loạt việc xung đột biên giới xảy ra sau vụ nổi dậy của Tây Tạng năm 1959, và việc Ấn Độ trao quy chế tỵ nạn chính trị cho Đức Đạt Lai Lạt Ma.

Ngày 20-10-1962

Trung Cộng đưa 80,000 quân đến mở hàng loạt những cuộc tấn công vào vùng Ladakh, đánh chiếm 2 vị trí của Ấn là Rezang La và Tawang.

Quân Ấn Độ tham chiến là 12,000. Đặc điểm của mặt trận là vùng rừng núi trên cao điểm 4,250m. Hai bên không xử dụng không quân và hải quân.

Trung Cộng thắng trận chiếm đất và tuyên bố ngừng bắn.

Tổn thất phía Trung Cộng:

- 1,460 người chết (Theo tài liệu TC)

- 2 người bị bắt

- 569 bị thương

Tổn thất phía Ấn Độ:

- 3,128 chết (Theo tài liệu của Ấn Độ)

- 3,123 bị bắt

- 1,047 bị thương

- 1,696 mất tích

9.3. Chiến tranh biên giới giữa Trung Cộng và Liên Xô

Dọc theo biên giới dài 4,380km Liên Xô bố trí 658,000 quân đối đầu với 814,000 quân Trung Cộng.

Ngày 2-3-1969

Lực lượng hai bên bất ngờ rơi vào xung đột. Hai nước đồng chí đổ thừa đối phương tấn công trước. Liên Xô chết 34 người, 14 bị thương. Lập tức phản công bằng đại bác, giết chết 800 trung cộng. Phía Liên Xô có 60 người, vừa chết vừa bị thương.

Sau vài trận đụng độ tiếp theo, hai bên chuẩn bị đối đầu bằng vũ khí nguyên tử. Sau đó tranh chấp tạm ngừng nhưng hai bên vẫn còn gờm nhau.

Ngày 17-10-1995

Hai đồng chí đạt được một thỏa thuận về đường biên giới dài 54km, nhưng 3 hòn đảo trên hai con sông Amur và Argun bị bỏ ra ngoài vòng giải quyết.

Ngày 27-4-2005

Một thỏa thuận được ký kết giữa hai bên, xem như tranh chấp cuối cùng được giải quyết.

Nga rất lo ngại Trung Cộng. Bình luận gia quân sự Nga là Anatoly Tsyganok Dmitrievich, Viện sĩ Hàn Lâm Viện Khoa học quân sự, Giám đốc Trung tâm dự báo quân sự, bình luận về Trung Cộng như sau: “Sau 15 năm nữa, thậm chí có thể sớm hơn, TQ sẽ trở thành một đối thủ quân sự nguy hiểm của nước Nga. Trong cuộc diễn tập quân sự hỗn hợp năm 2005 ở bán đảo Sơn Đông, các chuyên gia Nga ngẫu nhiên nhìn thấy bản đồ tác chiến của TQ. Trên bản đồ màu vàng được phủ kín toàn bộ vùng Siberia, Kazakhstan và Trung Á. TQ coi khu vực nầy đã bị Nga chiếm hơn 300 năm trước. 80% vũ khí của TQ toàn là vũ khí hiện đại nhất của Nga, cho nên không thua kém Nga chút nào cả. Trong quá khứ, TQ là một nước hiếu chiến và rất nguy hiểm đối với các nước láng giềng. Nga đã hiểu rõ điều đó”.

Nước Nga chỉ có một hải cảng duy nhất đi ra Thái Bình Dương ở phía Đông là Vladivostok, nằm sát bên phần đất Mãn Châu của Trung Cộng. Nếu hải cảng bị mất, thì kinh tế Nga bị ảnh hưởng trầm trọng trong việc xuất và nhập cảng hàng hoá. Đó là tử huyệt của Nga.

Trong thời gian hai đồng chí Cộng sản tận tình đánh giết nhau, thì CSVN vẫn tiến hành xây dựng Chủ Nghĩa Xã Hội để đưa nhân loại tiến tới đại đồng, như Hồ Chí Minh tuyên bố với “ông bạn” Trần Hưng Đạo “Bác đưa một nước qua nô lệ. Tôi dẫn năm châu đến đại đồng”. Bây giờ mới lòi cái mặt xảo trá của đảng CS “quang vinh” là như thế đó.

Về biên giới, TC có đường biên giới trên bộ tổng cộng 22,000km tiếp giáp với 14 quốc gia như Bắc Hàn, Ấn Độ, Nga, VN…

Chủ nghĩa bành trướng Đại Hán đã cai trị VN hơn 10 thế kỷ, kể từ thế kỷ thứ 2 TCN đến những thế kỷ sau, qua các triều đại Tần, Triệu, Hán, Ngô, Đường, Tống, Nguyên, Minh, Thanh và Mao Trạch Đông của đảng CSTQ.

9.1. Trung Cộng chiếm Tây Tạng

Tháng 10 năm 1950

TC đem 40,000 quân tấn công Tây Tạng cùng một lúc ở 6 vị trí, chỉ trong 2 ngày, TC giết trên 4,000 người trong một đạo quân bé nhỏ 8,000 người của Tây Tạng.

Ngày 9-9-1951

TC đem 23,000 quân chiếm đóng và cai trị Tây Tạng từ đó đến nay.

Tháng 3 năm 1959

Một cuộc nổi dậy chống TC bị thất bại ở Thủ đô Lhassa, Đức Đạt Lai Lạt Ma và hàng ngàn người Tây Tạng đến nương náu ở vùng Tây Bắc Ấn Độ, tập trung ở bang Himachal Pradesh, điều nầy khiến cho TC khó chịu.

Việc TC chiếm Tây Tạng là một đòn nặng đối với bản thân Thủ tướng Jawaharlal Nehru của Ấn Độ vì ông chủ trương “Thuyết Sống chung hoà bình”. Tuy bị chỉ trích là ngây thơ và yếu hèn, nhưng ông Nehru vẫn cố gắng “dĩ hoà vi quý”, nhường nhịn, lập bang giao với TC. TC nêu khẩu hiệu “Hindi-Chini bhai-bhai”, có nghĩa là “Ấn Độ và Trung Cộng là anh em”. Cũng giống như khẩu hiệu 16 chữ vàng và 4 tốt đối với VN hiện nay.

Nhưng tình huynh đệ chỉ kéo dài được vài năm, thì TC đem quân tấn công chiếm lãnh thổ Ấn Độ.

9.2. Trung Cộng đánh chiếm lãnh thổ Ấn Độ năm 1962

Nguyên nhân chính là việc tranh chấp biên giới vùng Aksai Chin và bang Arunachal Pradesh mà TC gọi là Nam Tây Tạng. Ngoài ra, còn những nguyên nhấn khác, như hàng loạt việc xung đột biên giới xảy ra sau vụ nổi dậy của Tây Tạng năm 1959, và việc Ấn Độ trao quy chế tỵ nạn chính trị cho Đức Đạt Lai Lạt Ma.

Ngày 20-10-1962

Trung Cộng đưa 80,000 quân đến mở hàng loạt những cuộc tấn công vào vùng Ladakh, đánh chiếm 2 vị trí của Ấn là Rezang La và Tawang.

Quân Ấn Độ tham chiến là 12,000. Đặc điểm của mặt trận là vùng rừng núi trên cao điểm 4,250m. Hai bên không xử dụng không quân và hải quân.

Trung Cộng thắng trận chiếm đất và tuyên bố ngừng bắn.

Tổn thất phía Trung Cộng:

- 1,460 người chết (Theo tài liệu TC)

- 2 người bị bắt

- 569 bị thương

Tổn thất phía Ấn Độ:

- 3,128 chết (Theo tài liệu của Ấn Độ)

- 3,123 bị bắt

- 1,047 bị thương

- 1,696 mất tích

9.3. Chiến tranh biên giới giữa Trung Cộng và Liên Xô

Dọc theo biên giới dài 4,380km Liên Xô bố trí 658,000 quân đối đầu với 814,000 quân Trung Cộng.

Ngày 2-3-1969

Lực lượng hai bên bất ngờ rơi vào xung đột. Hai nước đồng chí đổ thừa đối phương tấn công trước. Liên Xô chết 34 người, 14 bị thương. Lập tức phản công bằng đại bác, giết chết 800 trung cộng. Phía Liên Xô có 60 người, vừa chết vừa bị thương.

Sau vài trận đụng độ tiếp theo, hai bên chuẩn bị đối đầu bằng vũ khí nguyên tử. Sau đó tranh chấp tạm ngừng nhưng hai bên vẫn còn gờm nhau.

Ngày 17-10-1995

Hai đồng chí đạt được một thỏa thuận về đường biên giới dài 54km, nhưng 3 hòn đảo trên hai con sông Amur và Argun bị bỏ ra ngoài vòng giải quyết.

Ngày 27-4-2005

Một thỏa thuận được ký kết giữa hai bên, xem như tranh chấp cuối cùng được giải quyết.

Nga rất lo ngại Trung Cộng. Bình luận gia quân sự Nga là Anatoly Tsyganok Dmitrievich, Viện sĩ Hàn Lâm Viện Khoa học quân sự, Giám đốc Trung tâm dự báo quân sự, bình luận về Trung Cộng như sau: “Sau 15 năm nữa, thậm chí có thể sớm hơn, TQ sẽ trở thành một đối thủ quân sự nguy hiểm của nước Nga. Trong cuộc diễn tập quân sự hỗn hợp năm 2005 ở bán đảo Sơn Đông, các chuyên gia Nga ngẫu nhiên nhìn thấy bản đồ tác chiến của TQ. Trên bản đồ màu vàng được phủ kín toàn bộ vùng Siberia, Kazakhstan và Trung Á. TQ coi khu vực nầy đã bị Nga chiếm hơn 300 năm trước. 80% vũ khí của TQ toàn là vũ khí hiện đại nhất của Nga, cho nên không thua kém Nga chút nào cả. Trong quá khứ, TQ là một nước hiếu chiến và rất nguy hiểm đối với các nước láng giềng. Nga đã hiểu rõ điều đó”.

Nước Nga chỉ có một hải cảng duy nhất đi ra Thái Bình Dương ở phía Đông là Vladivostok, nằm sát bên phần đất Mãn Châu của Trung Cộng. Nếu hải cảng bị mất, thì kinh tế Nga bị ảnh hưởng trầm trọng trong việc xuất và nhập cảng hàng hoá. Đó là tử huyệt của Nga.

Trong thời gian hai đồng chí Cộng sản tận tình đánh giết nhau, thì CSVN vẫn tiến hành xây dựng Chủ Nghĩa Xã Hội để đưa nhân loại tiến tới đại đồng, như Hồ Chí Minh tuyên bố với “ông bạn” Trần Hưng Đạo “Bác đưa một nước qua nô lệ. Tôi dẫn năm châu đến đại đồng”. Bây giờ mới lòi cái mặt xảo trá của đảng CS “quang vinh” là như thế đó.

10* Kho vũ khí hạt nhân của các nước

Còn gọi là vũ khí nguyên tử, là vũ khí hủy diệt hàng loạt (Mass destruction), sức công phá của nó do sự phản ứng phân hạch hạt nhân của chất Uranium hoặc chất Plutonium.

Những quốc gia có vũ khí nguyên tử là Hoa Kỳ, Nga, Trung Cộng, Anh, Pháp, Ấn Độ, Pakistan, Do Thái. Ba nưóc Ấn Độ, Pakistan, Do Thái không ký tên trong Hiệp Ước Không phổ biến vũ khí hạt nhân (Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty-NNPT ngày 1-6-1968) vì cho rằng, mục đích của hiệp ước là, các nước đã có vũ khí hạt nhân muốn hạn chế những nước chưa có mà thôi.

Bắc Hàn trước kia đã ký hiệp ước, nhưng đến ngày 10-1-2003 thì rút tên ra khỏi hiệp ước, và đến ngày 10-2-2005, thì tuyên bố đã sở hữu thứ vũ khí nầy.

10.1. Số lượng vũ khí hạt nhân các nước

Các nhà quan sát cho rằng:

- Do Thái hiện có khoảng 200 đầu đạn hạt nhân.

- Pakistan: từ 60 đến 100 đơn vị

- Ấn Độ: từ 100 đến 120.(Hoả tiễn Agni I, II, III, IV, V)

- Trung Cộng: từ 237 đến 246. Sẽ có thêm 192 đầu đạn hạt nhân trên biển trong 5 năm tới.

10.2. Vũ khí hạt nhân của Hoa Kỳ và Nga

Ngày 8-4-2010, Tổng thống HK Barack Obama và TT Nga Dmitry Anatolyevich Medvedev ký Hiệp Ước cắt giảm vũ khí chiến lược (Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty-START) tại Thủ đô Prague của Cộng hoà Czech. Sau khi được phê chuẩn, hiệp ước tên START NEW bắt đầu có hiệu lực kể từ ngày 5-2-2011, kéo dài trong 10 năm, đến năm 2021, trong thời gian đó, hai bên đồng ý cắt giảm 84%, để mỗi bên chỉ còn 1,550 đầu đạn hạt nhân sau 7 năm.

Con số thống kê ngày 1-7-2009 thì:

- Hoa Kỳ có 13,825. (*Thời cao điểm nhất năm 1967, HK có 31,225 đầu đạn hạt nhân)

- Nga có: 10,292 đầu đạn.

Còn gọi là vũ khí nguyên tử, là vũ khí hủy diệt hàng loạt (Mass destruction), sức công phá của nó do sự phản ứng phân hạch hạt nhân của chất Uranium hoặc chất Plutonium.

Những quốc gia có vũ khí nguyên tử là Hoa Kỳ, Nga, Trung Cộng, Anh, Pháp, Ấn Độ, Pakistan, Do Thái. Ba nưóc Ấn Độ, Pakistan, Do Thái không ký tên trong Hiệp Ước Không phổ biến vũ khí hạt nhân (Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty-NNPT ngày 1-6-1968) vì cho rằng, mục đích của hiệp ước là, các nước đã có vũ khí hạt nhân muốn hạn chế những nước chưa có mà thôi.

Bắc Hàn trước kia đã ký hiệp ước, nhưng đến ngày 10-1-2003 thì rút tên ra khỏi hiệp ước, và đến ngày 10-2-2005, thì tuyên bố đã sở hữu thứ vũ khí nầy.

10.1. Số lượng vũ khí hạt nhân các nước

Các nhà quan sát cho rằng:

- Do Thái hiện có khoảng 200 đầu đạn hạt nhân.

- Pakistan: từ 60 đến 100 đơn vị

- Ấn Độ: từ 100 đến 120.(Hoả tiễn Agni I, II, III, IV, V)

- Trung Cộng: từ 237 đến 246. Sẽ có thêm 192 đầu đạn hạt nhân trên biển trong 5 năm tới.

10.2. Vũ khí hạt nhân của Hoa Kỳ và Nga

Ngày 8-4-2010, Tổng thống HK Barack Obama và TT Nga Dmitry Anatolyevich Medvedev ký Hiệp Ước cắt giảm vũ khí chiến lược (Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty-START) tại Thủ đô Prague của Cộng hoà Czech. Sau khi được phê chuẩn, hiệp ước tên START NEW bắt đầu có hiệu lực kể từ ngày 5-2-2011, kéo dài trong 10 năm, đến năm 2021, trong thời gian đó, hai bên đồng ý cắt giảm 84%, để mỗi bên chỉ còn 1,550 đầu đạn hạt nhân sau 7 năm.

Con số thống kê ngày 1-7-2009 thì:

- Hoa Kỳ có 13,825. (*Thời cao điểm nhất năm 1967, HK có 31,225 đầu đạn hạt nhân)

- Nga có: 10,292 đầu đạn.

11* Những vấn nạn của Ấn Độ

Ngày 17-5-2011, trong bài viết tựa đề “Trung Quốc là bạn hay thù của Ấn Độ?”, nhà nghiên cứu, TS Shashank Joshi nêu vấn đề như sau:

Giới cầm quyền và các nhà chiến lược quân sự Ấn, hiện có hai quan điểm trái ngược nhau về mối quan hệ giữa Trung Quốc và Ấn Độ. Quan điểm cứng rắn của giới quân sự cho rằng TQ là mối đe dọa, là kẻ thù của Ấn Độ. Quan điểm của giới cầm quyền dân sự thì cho rằng quan hệ giữa hai nước hoàn toàn có thể giải quyết bằng ngoại giao. Lãnh đạo dân sự tin tưởng vào “sự trổi dậy hòa bình” của TQ.

Giới quân sự chỉ trích rằng,

Ấn Độ đang bị thống trị bởi “chế độ dân sự cực đoan”, yếu kém về ý chí và tin tưởng hão huyền. Thủ tướng Manmohan Singh bị chỉ trích là quá cẩn trọng, tạo ra sự “thỏa hiệp” hơn là rào cản.

Năm 2009, nhà lãnh đạo quân đội là Bharat Verma, biên tập của tờ báo danh tiếng Indian Defense Review, tuyên bố bi đát rằng “TQ sẽ tấn công trước năm 2012, sẽ dạy cho Ấn Độ một bài học cuối cùng, để từ đó khẳng định uy thế độc tôn của mình ở châu Á trong thế kỷ 21.”

Ông Vikram Sood, cựu lãnh đạo cơ quan tình báo đã viết “TQ quyết tâm làm cho chúng ta bị tật nguyền về tâm lý và chiến lược”.

Trong nhiều năm qua, cơ quan tình báo Ấn Độ được Anh và Hoa Kỳ giúp đở, nâng cao khả năng thu thập tin tức tình báo Trung Cộng, do đó, nhân viên của cơ quan nầy đã nhận ra TC là kẻ thù nguy hiểm của Ấn Độ.

Trong cuộc thăm dò dư luận mới đây, trong 10 người được hỏi, thì chỉ có 4 người cho rằng TC là mối đe dọa nghiêm trọng.

Giới cầm quyền và các nhà chiến lược quân sự Ấn, hiện có hai quan điểm trái ngược nhau về mối quan hệ giữa Trung Quốc và Ấn Độ. Quan điểm cứng rắn của giới quân sự cho rằng TQ là mối đe dọa, là kẻ thù của Ấn Độ. Quan điểm của giới cầm quyền dân sự thì cho rằng quan hệ giữa hai nước hoàn toàn có thể giải quyết bằng ngoại giao. Lãnh đạo dân sự tin tưởng vào “sự trổi dậy hòa bình” của TQ.

Giới quân sự chỉ trích rằng,

Ấn Độ đang bị thống trị bởi “chế độ dân sự cực đoan”, yếu kém về ý chí và tin tưởng hão huyền. Thủ tướng Manmohan Singh bị chỉ trích là quá cẩn trọng, tạo ra sự “thỏa hiệp” hơn là rào cản.

Năm 2009, nhà lãnh đạo quân đội là Bharat Verma, biên tập của tờ báo danh tiếng Indian Defense Review, tuyên bố bi đát rằng “TQ sẽ tấn công trước năm 2012, sẽ dạy cho Ấn Độ một bài học cuối cùng, để từ đó khẳng định uy thế độc tôn của mình ở châu Á trong thế kỷ 21.”

Ông Vikram Sood, cựu lãnh đạo cơ quan tình báo đã viết “TQ quyết tâm làm cho chúng ta bị tật nguyền về tâm lý và chiến lược”.

Trong nhiều năm qua, cơ quan tình báo Ấn Độ được Anh và Hoa Kỳ giúp đở, nâng cao khả năng thu thập tin tức tình báo Trung Cộng, do đó, nhân viên của cơ quan nầy đã nhận ra TC là kẻ thù nguy hiểm của Ấn Độ.

Trong cuộc thăm dò dư luận mới đây, trong 10 người được hỏi, thì chỉ có 4 người cho rằng TC là mối đe dọa nghiêm trọng.

|

Bài học của thủ tướng Jawaharlal Nehru với chủ trương “sống chung hoà bình” đã đưa Ấn Độ đến những bại trận nhục nhã, chỉ trong một trận đánh ngắn ngủi mà trên 3,000 binh sĩ Ấn Độ bị bắt làm tù binh và bị mất lãnh thổ, đã chưa làm cho các nhà lãnh đạo dân sự mở mắt ra.

12* Kết

Lịch sử của Trung Cộng chứng minh rằng bành trướng lãnh thổ là bản chất của Hán tộc, bản chất nầy vẫn còn tiếp diễn cho đến ngày nay.

Ấn Độ có đủ điều kiện trở thành một cường quốc dân chủ ở châu Á. Trong báo cáo của Hội Đồng Tình Báo Quốc Gia HK, có ghi rằng, “Nếu kinh tế TQ chậm lại vài phần trăm (%) thì Ấn Độ sẽ nổi lên thành một nền kinh tế tăng trưởng nhanh nhất thế giới vào năm 2020. Điều nầy cho phép Ấn Độ trở thành một cường quốc quân sự”.

Cũng may, Thủ tướng Manmohan Singh đã nhận ra “người TQ có quyết đoán mới…vì vậy, chúng ta cần phải chuẩn bị”.

Bây giờ mới bắt đầu chuẩn bị thì hơi muộn, nhưng dù có còn hơn không

Trúc GiangẤn Độ có đủ điều kiện trở thành một cường quốc dân chủ ở châu Á. Trong báo cáo của Hội Đồng Tình Báo Quốc Gia HK, có ghi rằng, “Nếu kinh tế TQ chậm lại vài phần trăm (%) thì Ấn Độ sẽ nổi lên thành một nền kinh tế tăng trưởng nhanh nhất thế giới vào năm 2020. Điều nầy cho phép Ấn Độ trở thành một cường quốc quân sự”.

Cũng may, Thủ tướng Manmohan Singh đã nhận ra “người TQ có quyết đoán mới…vì vậy, chúng ta cần phải chuẩn bị”.

Bây giờ mới bắt đầu chuẩn bị thì hơi muộn, nhưng dù có còn hơn không

-------------------

China does some chest thumping

http://soodvikram.blogspot.com/search/label/China

China’s rulers have a problem. They are not sure if

they can continue to portray the image of a country interested in a

peaceful rise without this coming into direct conflict with a desire to

reassert newly defined core interests. All of 2010 saw a more assertive

Chinese foreign policy activity in its periphery, including India,

reflecting possibly a tussle of some sorts in Beijing between an

assertive People’s Liberation Army (PLA) which may want a bigger role in

foreign policy in the decade ahead, and a political leadership that is

now going to be in transition as Mr Hu Jintao prepares to hand over

power to his selected successor, Xi Jinping, by 2012? And therefore this

exercise of display of assertiveness with each power centre, notably

the PLA and the Party hierarchy, positioning themselves inside China and

positioning themselves against the US where there will be presidential

elections in end-2012.

China’s

assertiveness and the recent reactions in the Chinese media to the

visit of the Indian ship INS Airavat is only a reassertion of its

position. China had taken umbrage at US secretary of state Hillary

Clinton’s July 2010 remarks in Hanoi on creating an international

mechanism to resolve this issue, has been particularly visible in the

past few weeks. Earlier Dai Bingguo conveyed to Ms Clinton in May 2010

that China regarded its claims to the South China Sea as a core national

interest.

The

Chinese carried out a live ammunition PLA Navy exercise in the South

China Sea on July 26, 2010 followed by another exercise on August 3

along the Yellow Sea coast — the other area of contention. The Chinese

conducted exercises there in April and June this year, and were now

asserting that China opposed any foreign ships entering the sea or

adjacent waters; they even vehemently opposed joint US-South Korean

exercises there.

The

message in these demarches to the US was in keeping with protecting

China’s core interests in the adjacent seas and telling the US that the

western Pacific was China’s sphere of interest and influence. It

suggested a division of zones of influence between the Eastern and

Western Pacific. The US and China have their own geostrategic rivalries

to settle, and the Chinese may have assessed that their moment has come.

Its

reaction to the visit of the Indian ship has to be seen in this context

– it is part belief in its history, part knee jerk, part bullying, part

worry about energy resources, and part suspicion about growing

India-Vietnamese-US triangular relationship in the South China Sea. The

influential Communist Party-managed newspaper the Global Times was

somewhat hysterical when, in its editorial of September 16, it warned

India that any deal with Vietnam would be ‘serious political

provocation’ which could ‘push China to the limit’ and described the

ONGC Vietnam deal as a reflection of Indian ambitions. The newspaper

went on to say that while China was sincere about its peaceful rise it

will not give up its right to use other means to protect its interest.

China cherished its friendship with India but this did not mean that

China valued this above all else. It referred to India’s intervention in

the Dalai Lama issue and ends with the warning that ‘we should not

leave the world with the impression that China is only focused on

economic development nor should we pursue the reputation of being a

peaceful power,’... Clearly, there is a debate inside the sanctum

sanctorum of the Chinese Communist Party.

China’s

reaction is also a reflection of its concern for energy resources.

China has only 1.1% of the world’s known energy reserves but consumes

10.4 % of the world’s oil production and 20.1 % of the total energy

consumption in the world. The mismatch is obvious and will grow more in

the years ahead. Naturally, China views the disputed South China Sea

zone with its energy reserves with special interest. Some estimates

state that the known reserves of the South China Sea are twice as much

as China’s reserves of oil and there is plenty of gas too.

The

Indian reaction to this charge by Beijing has been firm pointing out

that India’s cooperation with Vietnam or with any other country ‘is

always as per international laws, norms and conventions...’ India has

also pointed out China’s role in the disputed part of POK under Pakistan

occupation where China may be on the verge of using the territory for

developing communication links with Afghanistan. Obviously, China is

planning for a post-US phase in Afghanistan, access to its mineral

resources, ultimately linking to Iran and the Gulf; it would not want

the region to be solely India’s sphere of influence. India has also to

keep its own vulnerabilities in Arunachal Pradesh in mind; even though

outright war is unlikely we should expect economic cooperation and

periodic tensions. China-India relations will not be determined by

strict bilateral terms. As both countries rise, there will be

competition in other spheres - for markets, resources and influence.

Yet

China remains concerned with its intricate trade and financial links

with the US, and also with the security of its trade and supply routes

that transit the Malacca Straits. It has endeavoured to develop

extensive land routes through Central Asia, but these are inadequate. It

is a matter of time before China will make its presence more visible in

the Indian Ocean. It has port facilities in Kyaukpyu, Hambantota and

Gwadar, and a presence in the Arabian Sea as it battles Somali pirates.

China has expanded its contacts with Iran and has developed strong ties

with Burma.

It

is of course entirely feasible that China would have reacted in this

manner even if there were not the question of energy reserves of South

China Sea. It would have had more to do with its own perception as

zhongguo – the “Middle Kingdom” or the “Central Country” where the

neighbouring countries were considered to be vassal states and who

accepted the Emperor in Beijing as the supreme power in the region.

Thus

while New Delhi agonises over challenges across land frontiers,

ignoring the new challenge in the Indian Ocean would be extremely hurt

Indian interests. There is need to plan counter measures in China's

periphery from now. Perpetual whining about China's grand designs will

not help.

Source : Written for ANI, New Delhi on September 21, 2011

Source : Written for ANI, New Delhi on September 21, 2011

Indo-U.S. relations series continues with Vikram Sood, May 7

When Lang Lang, a resident of New York, was invited by the White House

for a piano recital at the banquet for Chinese President Hu Jintao in

Washington DC on January 19, no one really bothered to check the music

he would play. The score he played had Mr Hu beaming and the Chinese

Internet users delighted.

According to commentators like Matthew Robertson, early morning TV viewers in China knew about an hour or so in advance that Lang Lang would play the song My Motherland. The melody selected by the pianist was the theme song from the 1956 Chinese propaganda film of Korean War days — Battle on Shangganling Mountain (Triangle Hill). The song refers to the Americans as “jackals” (some say it is “wolves”) and the victory at Triangle Hill was meant to depict victory over imperialists.

Quite obviously, Mr Hu’s hosts did not know the significance of the song. Apparently they were quite satisfied after the mandatory reprimand the US President had delivered to his guest when he spoke of the need for China to observe human rights so long as Mr Hu bought $45 billion worth of American goods. Whatever spin the Americans and the White House might put on this incident now, it is being seen as a great propaganda victory in China.

The question is, was this a carefully-choreographed plan by the Chinese who knew that they would receive the par-for-the-course lecture on human rights and values of democracy even as the two countries remain locked in a economic-trade-currency embrace, and the Americans had to be given an immediate response on their home ground? Or does this reflect a tussle of some sorts in Beijing between an assertive People’s Liberation Army (PLA), which may want a bigger role in foreign policy in the decade ahead, and a political leadership that is now going to be in transition as Mr Hu prepares to hand over power to his selected successor, Xi Jinping, by 2012? And therefore this exercise of display of assertiveness with each power centre positioning itself inside China and positioning themselves against the US where there will be presidential elections in 2012.

All of 2010 saw a more assertive Chinese foreign policy activity in its periphery, including India. The New Year began similarly when the Chinese arranged the leak about their new J-20 stealth fighter just hours ahead of US defence secretary Robert Gates’ meeting with President Hu on January 11 in Beijing. The word is that this fighter is based on US technology having got some of the technology from an American F-117 that was shot down in the Balkans in 1999. Apart from this, the Chinese also revealed that Shi Lang, the first of six Chinese aircraft carriers, will sail later this year; and the Dong Feng 21D missile, which is capable of sinking a US aircraft carrier, is now a part of the Chinese Second Artillery Corps arsenal. The message is that the western Pacific is more and more a Chinese domain. The gauntlet has been thrown by a China that has hubris as the other superpower on its way to attaining its pre-ordained position in the world.

If China’s military assertiveness is the new factor that worries the Pentagon, it is the Chinese quest for technology that has in many ways made this assertiveness possible today. China’s economic rise is not merely export driven. It is based on the principle and practice that to be competitive in the global economy, China would need to innovate and indigenise. Above all factors today, it is innovation that will drive growth and competitiveness, and this is only possible through a well-integrated education, research and infrastructure. Three years ago, the Chinese were the fourth-highest spenders on research and development at $66 billion. The concentration has been on hybrid electric vehicles, high-speed rail and solar power systems — the future for transport, energy and communications (American Progress, January 14, 2011, report). This is something we lack and a mere Nano and an LCA (Light Combat Aircraft, Tejas) are far too inadequate. They do not qualify as 21st century innovations.

Inevitably, a major event like the Hu visit evoked comments from the old cold warriors of the previous century, Henry Kissinger and Zbigniew Brzezinski. The former had broken the ice between Beijing and Washington and the latter had arranged the establishment of diplomatic relations between the two. Kissinger took the first step towards the creation of a rising China against the Soviets and now speaks of the need for the two countries to interact globally and avoid another Cold War. Mr Kissinger sees the need to build an emerging world order as a joint enterprise. Mr Brzezinski gave us the Afghan jihad that thrives today, and the few “Islamic hotheads” that he scorned at then have become a global menace. He too stressed on the need for the US and China to collaborate on global issues like North Korea and West Asia. This one supposes is a continuation of the G2 principle that US President Barack Obama first enunciated when he visited China in November 2009.

At first, seemingly lukewarm and reacting to President Obama’s meeting with the Dalai Lama and arms sales to Taiwan, China now assesses that its moment has come and demands that it be heard as an equal partner.

The Hu-Obama joint statement spoke of close cooperation on climate and energy problems and “deeper bilateral engagement and coordination” on “a wide range of security, economic, social, energy and environmental issues”. Platitudes apart, the two countries, despite their differences on economic issues, are expected to work together on many others. China may have risen for its neighbourhood but not enough to take on the US frontally.

The internal debate in the US whether China needs to be contained or engaged and co-opted will continue. Whichever way we look at it, China will engage the US attentions far more than India. Also, neither of these global powers will jeopardise their bilateral relations for India’s sake. In the final analysis, India is going to be fairly alone.

Source : Asian Age , 25th January 2011, Vikram Sood, Former Head of the Research and Analysis Wing, India’s external intelligence agency

According to commentators like Matthew Robertson, early morning TV viewers in China knew about an hour or so in advance that Lang Lang would play the song My Motherland. The melody selected by the pianist was the theme song from the 1956 Chinese propaganda film of Korean War days — Battle on Shangganling Mountain (Triangle Hill). The song refers to the Americans as “jackals” (some say it is “wolves”) and the victory at Triangle Hill was meant to depict victory over imperialists.

Quite obviously, Mr Hu’s hosts did not know the significance of the song. Apparently they were quite satisfied after the mandatory reprimand the US President had delivered to his guest when he spoke of the need for China to observe human rights so long as Mr Hu bought $45 billion worth of American goods. Whatever spin the Americans and the White House might put on this incident now, it is being seen as a great propaganda victory in China.

The question is, was this a carefully-choreographed plan by the Chinese who knew that they would receive the par-for-the-course lecture on human rights and values of democracy even as the two countries remain locked in a economic-trade-currency embrace, and the Americans had to be given an immediate response on their home ground? Or does this reflect a tussle of some sorts in Beijing between an assertive People’s Liberation Army (PLA), which may want a bigger role in foreign policy in the decade ahead, and a political leadership that is now going to be in transition as Mr Hu prepares to hand over power to his selected successor, Xi Jinping, by 2012? And therefore this exercise of display of assertiveness with each power centre positioning itself inside China and positioning themselves against the US where there will be presidential elections in 2012.

All of 2010 saw a more assertive Chinese foreign policy activity in its periphery, including India. The New Year began similarly when the Chinese arranged the leak about their new J-20 stealth fighter just hours ahead of US defence secretary Robert Gates’ meeting with President Hu on January 11 in Beijing. The word is that this fighter is based on US technology having got some of the technology from an American F-117 that was shot down in the Balkans in 1999. Apart from this, the Chinese also revealed that Shi Lang, the first of six Chinese aircraft carriers, will sail later this year; and the Dong Feng 21D missile, which is capable of sinking a US aircraft carrier, is now a part of the Chinese Second Artillery Corps arsenal. The message is that the western Pacific is more and more a Chinese domain. The gauntlet has been thrown by a China that has hubris as the other superpower on its way to attaining its pre-ordained position in the world.

If China’s military assertiveness is the new factor that worries the Pentagon, it is the Chinese quest for technology that has in many ways made this assertiveness possible today. China’s economic rise is not merely export driven. It is based on the principle and practice that to be competitive in the global economy, China would need to innovate and indigenise. Above all factors today, it is innovation that will drive growth and competitiveness, and this is only possible through a well-integrated education, research and infrastructure. Three years ago, the Chinese were the fourth-highest spenders on research and development at $66 billion. The concentration has been on hybrid electric vehicles, high-speed rail and solar power systems — the future for transport, energy and communications (American Progress, January 14, 2011, report). This is something we lack and a mere Nano and an LCA (Light Combat Aircraft, Tejas) are far too inadequate. They do not qualify as 21st century innovations.

Inevitably, a major event like the Hu visit evoked comments from the old cold warriors of the previous century, Henry Kissinger and Zbigniew Brzezinski. The former had broken the ice between Beijing and Washington and the latter had arranged the establishment of diplomatic relations between the two. Kissinger took the first step towards the creation of a rising China against the Soviets and now speaks of the need for the two countries to interact globally and avoid another Cold War. Mr Kissinger sees the need to build an emerging world order as a joint enterprise. Mr Brzezinski gave us the Afghan jihad that thrives today, and the few “Islamic hotheads” that he scorned at then have become a global menace. He too stressed on the need for the US and China to collaborate on global issues like North Korea and West Asia. This one supposes is a continuation of the G2 principle that US President Barack Obama first enunciated when he visited China in November 2009.

At first, seemingly lukewarm and reacting to President Obama’s meeting with the Dalai Lama and arms sales to Taiwan, China now assesses that its moment has come and demands that it be heard as an equal partner.

The Hu-Obama joint statement spoke of close cooperation on climate and energy problems and “deeper bilateral engagement and coordination” on “a wide range of security, economic, social, energy and environmental issues”. Platitudes apart, the two countries, despite their differences on economic issues, are expected to work together on many others. China may have risen for its neighbourhood but not enough to take on the US frontally.

The internal debate in the US whether China needs to be contained or engaged and co-opted will continue. Whichever way we look at it, China will engage the US attentions far more than India. Also, neither of these global powers will jeopardise their bilateral relations for India’s sake. In the final analysis, India is going to be fairly alone.

Source : Asian Age , 25th January 2011, Vikram Sood, Former Head of the Research and Analysis Wing, India’s external intelligence agency

China asserts itself

For decades China pretended to be modest and Deng Xiaoping’s successors

followed him as they couched their ambitions in soft idioms. The “sons

of heaven”, as the Chinese traditionally consider themselves, also

consider those on their periphery as rebellious barbarians who had to be

tamed or conquered. So the discourse was: “Tao guang yang hui” —

variously translated, but which essentially means “hide brightness,

nourish obscurity”. The exhortation was to keep a low profile when in an

adverse situation and wait for a suitable opportunity to reverse

fortunes. The other advice was “yield on small issues with the long term

in mind”. All this has begun to change as China’s influence began to

rise and the United States was perceived to be in decline. The US policy

predicaments in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran and Western economic

crises in contrast to China’s steady growth is probably the reason for

this change in attitude. There is an exuberance and global

self-confidence accompanied by a global outreach that was not visible

earlier.

It is useful to go back to January 20, 2009 — the day Barack Obama was sworn in as US President. This was also the day that the Chinese released their White Paper on National Defence (2008). Perhaps a coincidence, perhaps not. The White Paper covers issues like Taiwan, Tibet, the defence budget, diplomatic outreach and gives some details about how China would use its nuclear force. It is important to refer to some portions of the paper which underline the new philosophy. The preface mentions that historic changes were taking place between contemporary China and the rest of the world, and the Chinese had become an important part of the international system. China, it said, “could not develop in isolation from the rest of the world, nor can the world enjoy prosperity and stability without China.” The intention was to portray China as a participatory nation with huge responsibilities and its own indispensability in the new global order.

China’s international behaviour has been a mix of defiance — such as at the Copenhagen climate summit, when it sent junior functionaries to discussions with heads of state, or its dealings on the Iran nuclear issue or the nuclear deal with Pakistan. China has been assertive with India on Arunachal Pradesh by blocking the ADB loan, has been provocative by issuing “plain paper” visas to Indians born in Jammu and Kashmir and routinely shrill about the Dalai Lama, while increased border violations have been noticed in Arunachal Pradesh — which Chinese commentators call “Southern Tibet”. Chinese activities in our neighbourhood, its plans to dam the Brahmaputra and extend the Tibet rail link into Nepal are other aspects of continuing Chinese assertiveness. The Chinese PLA had recently transported combat readiness material to PLA and Air Force units in Tibet by rail for the first time. This would further enhance the military transportation capacity, apart from the construction of more airports in Tibet.

While some American experts like Prof. David Shambaugh describe this Chinese attitude as a sign of defensive nationalism — assertive in form but reactive in essence, the fact is that since about the middle of 2009 the Chinese have talking more and more about their “core interests”. As D.S. Rajan, director of the Centre for China Studies, Chennai, points out, Chinese leader Dai Bingguo said in July 2009 that “the PRC’s first core interest is maintaining its fundamental system and state security, the second is state sovereignty and territorial integrity, and the third is the continued stable development of the economy and society”. Translated into specifics, it means protection of its interests in Tibet, Taiwan, Xinjiang, the South China Sea and its strategic resources and sea trade routes.

China’s assertiveness about the South China Sea, its umbrage at US secretary of state Hillary Clinton’s July 2010 remarks in Hanoi on creating an international mechanism to resolve this issue, has been particularly visible in the past few weeks. Dai Bingguo conveyed to Ms Clinton in May 2010 that China regarded its claims to the South China Sea as a core national interest. The Chinese have closely watched the growing US-Vietnamese ties, which includes an American offer of a civil nuclear deal to Vietnam on lines similar to the India deal. A triangular acrimony between the US, China and Vietnam has been growing for some time.

The Chinese carried out a live ammunition PLA Navy exercise in the South China Sea on July 26, followed by another exercise on August 3 along the Yellow Sea coast — the other area of contention. The Chinese conducted exercises there in April and June this year, and were now asserting that China opposed any foreign ships entering the sea or adjacent waters; they even vehemently opposed joint US-South Korean exercises there.

The message in these demarches to the US was in keeping with protecting China’s core interests in the adjacent seas and telling the US that the western Pacific was China’s sphere of interest and influence. It suggested a division of zones of influence between the Eastern and Western Pacific. The US and China have their own geostrategic rivalries to settle, and the Chinese may have assessed that their moment has come.

Yet China remains concerned with its intricate trade and financial links with the US, and also with the security of its trade and supply routes that transit the Malacca Straits. It has endeavoured to develop extensive land routes through Central Asia, but these are inadequate. It is a matter of time before China will make its presence more visible in the Indian Ocean. It has port facilities in Hambantota and Gwadar, and a presence in the Arabian Sea as it battles Somali pirates. China has expanded its contacts with Iran, more in competition with Russia than the US, it seeks mineral wealth in Afghanistan, its relations with Pakistan need no elucidation and it has developed strong ties with Burma. Thus while we may agonise over challenges across our land frontiers, we would be ignoring the new challenge in the Indian Ocean unless we plan countermeasures now.

Source : Asian Age , 25th August 2010

It is useful to go back to January 20, 2009 — the day Barack Obama was sworn in as US President. This was also the day that the Chinese released their White Paper on National Defence (2008). Perhaps a coincidence, perhaps not. The White Paper covers issues like Taiwan, Tibet, the defence budget, diplomatic outreach and gives some details about how China would use its nuclear force. It is important to refer to some portions of the paper which underline the new philosophy. The preface mentions that historic changes were taking place between contemporary China and the rest of the world, and the Chinese had become an important part of the international system. China, it said, “could not develop in isolation from the rest of the world, nor can the world enjoy prosperity and stability without China.” The intention was to portray China as a participatory nation with huge responsibilities and its own indispensability in the new global order.

China’s international behaviour has been a mix of defiance — such as at the Copenhagen climate summit, when it sent junior functionaries to discussions with heads of state, or its dealings on the Iran nuclear issue or the nuclear deal with Pakistan. China has been assertive with India on Arunachal Pradesh by blocking the ADB loan, has been provocative by issuing “plain paper” visas to Indians born in Jammu and Kashmir and routinely shrill about the Dalai Lama, while increased border violations have been noticed in Arunachal Pradesh — which Chinese commentators call “Southern Tibet”. Chinese activities in our neighbourhood, its plans to dam the Brahmaputra and extend the Tibet rail link into Nepal are other aspects of continuing Chinese assertiveness. The Chinese PLA had recently transported combat readiness material to PLA and Air Force units in Tibet by rail for the first time. This would further enhance the military transportation capacity, apart from the construction of more airports in Tibet.

While some American experts like Prof. David Shambaugh describe this Chinese attitude as a sign of defensive nationalism — assertive in form but reactive in essence, the fact is that since about the middle of 2009 the Chinese have talking more and more about their “core interests”. As D.S. Rajan, director of the Centre for China Studies, Chennai, points out, Chinese leader Dai Bingguo said in July 2009 that “the PRC’s first core interest is maintaining its fundamental system and state security, the second is state sovereignty and territorial integrity, and the third is the continued stable development of the economy and society”. Translated into specifics, it means protection of its interests in Tibet, Taiwan, Xinjiang, the South China Sea and its strategic resources and sea trade routes.

China’s assertiveness about the South China Sea, its umbrage at US secretary of state Hillary Clinton’s July 2010 remarks in Hanoi on creating an international mechanism to resolve this issue, has been particularly visible in the past few weeks. Dai Bingguo conveyed to Ms Clinton in May 2010 that China regarded its claims to the South China Sea as a core national interest. The Chinese have closely watched the growing US-Vietnamese ties, which includes an American offer of a civil nuclear deal to Vietnam on lines similar to the India deal. A triangular acrimony between the US, China and Vietnam has been growing for some time.

The Chinese carried out a live ammunition PLA Navy exercise in the South China Sea on July 26, followed by another exercise on August 3 along the Yellow Sea coast — the other area of contention. The Chinese conducted exercises there in April and June this year, and were now asserting that China opposed any foreign ships entering the sea or adjacent waters; they even vehemently opposed joint US-South Korean exercises there.

The message in these demarches to the US was in keeping with protecting China’s core interests in the adjacent seas and telling the US that the western Pacific was China’s sphere of interest and influence. It suggested a division of zones of influence between the Eastern and Western Pacific. The US and China have their own geostrategic rivalries to settle, and the Chinese may have assessed that their moment has come.

Yet China remains concerned with its intricate trade and financial links with the US, and also with the security of its trade and supply routes that transit the Malacca Straits. It has endeavoured to develop extensive land routes through Central Asia, but these are inadequate. It is a matter of time before China will make its presence more visible in the Indian Ocean. It has port facilities in Hambantota and Gwadar, and a presence in the Arabian Sea as it battles Somali pirates. China has expanded its contacts with Iran, more in competition with Russia than the US, it seeks mineral wealth in Afghanistan, its relations with Pakistan need no elucidation and it has developed strong ties with Burma. Thus while we may agonise over challenges across our land frontiers, we would be ignoring the new challenge in the Indian Ocean unless we plan countermeasures now.

Source : Asian Age , 25th August 2010

Good fences make good neighbours or as the Economist of London once put

it in the context of US-Mexico border, "good neighbours make fences".

Yet India and China, the two most populous countries of the world, with

the largest standing armies, growing economies in competition, and, with

two nuclear weapon powers aligned against us in a

higher-than-the-Himalayas friendship, we do not even have the

4,057-kilometre land frontier delineated. Demarcation is a long way off.

It is wishful thinking that the burgeoning trade between the two countries will compensate for any lack of political depth in our relationship despite all the talk of strategic partnerships, a joint mechanism on counter-terror and joint military exercises. The hope held out is that improving trade and economic ties will pave the way for future reconciliation. If it were that simple then the China-Japan political relationship would have been qualitatively different today. Despite the massive bilateral trade and despite massive Japanese investments in China, the underlying political suspicions and age-old animosities have not disappeared.

So also with India and China. We do not seem to have recovered from our 1962 trauma and China is determined to keep us that way, psychologically and strategically handicapped. Even before India began to grow economically, China was intent on keeping India boxed in within its national boundaries. And now with growing competition for markets and resources, there is greater Chinese need to restrict India's reach and influence as a possible alternative and successful model of growth and governance. For long, Pakistan has been a low cost hedge for Chinese policymakers and the recent US-India warmth may worry Beijing even though it will continue to pretend public disdain.

China can be expected to maintain this posture so long as the Dalai Lama and the Tibet issue is not firmly solved in their favour. There are India China differences on Chinese nuclear, missile and military assistance to Pakistan. China will not give India the space it needs neither in the search for energy resources, markets or what India deems its rightful place on the High Table. Given the Chinese global position, its economic might and the US-Chinese interdependent relationship which neither will jeopardise for India's sake, the Chinese will not be in a hurry to resolve the boundary dispute.

It is India, therefore, that will have to set the pace. But this can only be done once there is a clear and honest appraisal of the nature of the problem, the issues involved and then think of possible solutions. This continued ambivalence sets in a lethargy that can be strategically self-defeating and India, therefore, needs a lasting solution. This is what Mohan Guruswamy and Zorawar Daulet Singh set out to do in their book India China Relations: the Border Issue and Beyond. The book is the result of a joint venture between the Centre for Policy Alternatives and the Observer Research Foundation, and its main advantage is that it is lucid, objective and well-argued; and the authors succinctly state their argument in about 140 pages apart from the appendices.